by Joyce Audy Zarins

In my small collection of children’s books from around the world, some help explain ways of thinking to the young. The world can be a scary and sometimes puzzling place, so clues are always useful.

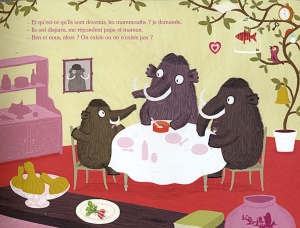

In Les Mammouths, Les Ogres, Les Extraterrestres, et ma petite soeur, as the title suggests, creatures of the past and future meet and the question of what is real and what is imaginary is raised. It is also self-referential. This Tom’poche publication originated in Nice, France and is written by Alex Cousseau and illustrated by Nathalie Choux with whimsical decorations that include many references to folk tales and other children’s stories. The colors are warm and bright and blend the possible with the impossible.

The existentialism begins with the first sentence, “Papa says that mammoths do not exist.†Well, considering that Papa appears to be that very species, albeit with a bow tie, the fun begins. Papa says that ogres don’t exist either. Mama adds that mammoths only existed a long, long time ago. So what about this nice family with their wide open eyes? The little mammoth asks, “Do you exist or not?â€

The existentialism begins with the first sentence, “Papa says that mammoths do not exist.†Well, considering that Papa appears to be that very species, albeit with a bow tie, the fun begins. Papa says that ogres don’t exist either. Mama adds that mammoths only existed a long, long time ago. So what about this nice family with their wide open eyes? The little mammoth asks, “Do you exist or not?â€

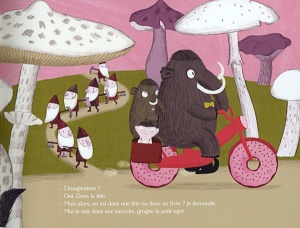

Papa explains as they walk out on the street and into the world that they only exist when the author of the book writes their story and the illustrator draws it so. In spite of appearances, they are not really on the street or in the world. If the author wants to show on the street an ogre on top of a sheep, he will ask the artist to draw that. Little mammoth notes that the result looks more like a green extraterrestrial than an ogre. Papa concurs. That is because the artist lady is not so good at drawing ogres. She is very good at drawing sheep, though.

The little guy with the red pants turns out to be the ogre and imagine his surprise when he is riding in the pannier of Papa Mammoth’s doughnut-wheeled motorcycle and overhears that he doesn’t exist either! Imaginative adventures happen. Past, present, and future collide and there is a lovely mix of realistic artichoke roofs on buildings and doll-faced characters (one of whom is reading the very book we’re discussing) dancing across the pages with the Seven Dwarfs, a blind mouse, and lots of other improbables.

The little guy with the red pants turns out to be the ogre and imagine his surprise when he is riding in the pannier of Papa Mammoth’s doughnut-wheeled motorcycle and overhears that he doesn’t exist either! Imaginative adventures happen. Past, present, and future collide and there is a lovely mix of realistic artichoke roofs on buildings and doll-faced characters (one of whom is reading the very book we’re discussing) dancing across the pages with the Seven Dwarfs, a blind mouse, and lots of other improbables.

At the end of this philosophical day, the little mammoth mentions something else suggested by the book’s title. “I would love to have a little sister.†But that won’t happen unless the author thinks of it and writes her into the book and the artist draws her, right? No, Papa explains. The little sister will only exist when Papa and Mama wink to each other. This is the way it always begins.

This is a completely delightful book, and I know for a fact that it does actually exist.

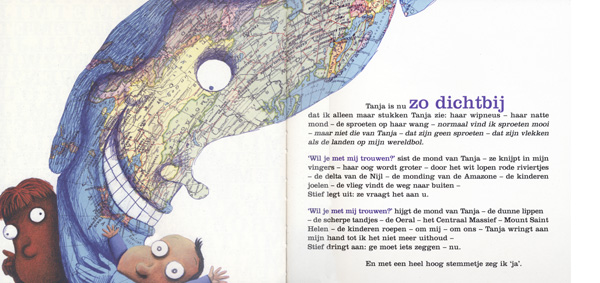

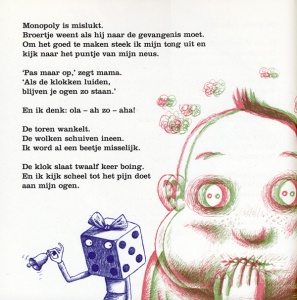

In Trouwen met Tanja (Married with Tanja) by Bart Van Nuffelen and Klaas Verplancke there is also a huge emphasis on the written word, but in a different way. For example, the endpapers are covered with a child’s cursive writing that repeats endlessly, “I will not marry Tanja.†The typography throughout the book uses scale and color changes to emphasize the action and meaning of the story using Clarendon type. And the underlying message regards keeping your word, though maybe not when your promise has been coerced.

On Marc’s last day of kindergarten before a vacation he and the other kids are doing foolish things, running in circles until they see stars and so on. Along comes Stief, who is grosser than most, especially about bodily functions. He also knows more about the female anatomy than anyone. He imitates a robot making everyone laugh and Marc falls to the ground with the hilarity of it all.

On Marc’s last day of kindergarten before a vacation he and the other kids are doing foolish things, running in circles until they see stars and so on. Along comes Stief, who is grosser than most, especially about bodily functions. He also knows more about the female anatomy than anyone. He imitates a robot making everyone laugh and Marc falls to the ground with the hilarity of it all.

He feels someone grab him – first by his neck, then in other places. It is Tanja. She is silent, then she gently asks him, “Will you marry me?â€

She looks weird to Mark because she’s so close. He can only see a bit of her at a time. Her freckles remind him of countries on the globe and he feels like a fly caught in a spiderweb. She asks again and he says no. She squeezes his fingers. Her sharp teeth remind him of the Ural mountains, the Central Massif…even Mount Saint Helen. Steif yells at him to answer her and under pressure he caves in and squeaks out a “yes.†Oh no. What did he do?

During vacation Marc tries outlandish ways to change his bad luck, because he does not want to marry Tanja. When he asks Mom and Dad what happens if you promise… Mom interrupts and says he must keep his promise. Marc feels doomed. He decides to hold his breath until it isn’t true anymore. That doesn’t work. He tries other tricks. Nothing. Zorro, who is Stief in disguise, appears and gives him a clue. And the saga continues. This goes on through the entire vacation, then once back at school, there she is again, the inescapable Tanja. Amid kids chanting and other chaos, The chant from the beginning of the book is repeated and Marc flies head over heels off toward America to escape.

During vacation Marc tries outlandish ways to change his bad luck, because he does not want to marry Tanja. When he asks Mom and Dad what happens if you promise… Mom interrupts and says he must keep his promise. Marc feels doomed. He decides to hold his breath until it isn’t true anymore. That doesn’t work. He tries other tricks. Nothing. Zorro, who is Stief in disguise, appears and gives him a clue. And the saga continues. This goes on through the entire vacation, then once back at school, there she is again, the inescapable Tanja. Amid kids chanting and other chaos, The chant from the beginning of the book is repeated and Marc flies head over heels off toward America to escape.

The mixed media images are large-scale madcap exaggerations which makes them completely engaging, especially Tanja as a global entity. And everyone’s eyes are the same bugging-out-of-their-heads type as those in the previously described book – round white circles with expressive black pupils. The illustration colors used are deep tones that make the compositions pop.

The drama is clear and the characters certainly emote.

Jako by se tu nekdo snazil nevydat ani hlasku (A Sound Like Someone Trying Not to Make a Sound) by John Irving, illustrated by Tatjana Hauptmannova, was translated from the original English by Meander publishers, Czech Republic. It was originally published by Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

This picture book was first told within Mr. Irvings’ novel A Widow for One Year, which was made into the movie The Door in The Floor. In it, the main character is a children’s book writer named Ted Cole. According to an interview with Mr. Irving, he did not set out to write a children’s book until he needed some examples to attribute to the main character of his novel. Does this suggest similarities with the Les Mammouths version of reality?

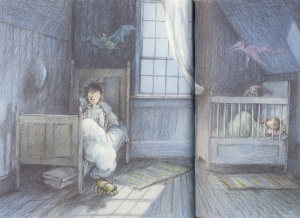

In the picture book story, Tom is awakened in the middle of the night by a sound. He sits bolt upright in bed, eyes wide and bulging. What was that? We can imagine the pounding of his heart. He can’t identify what the sound is because it isn’t like anything he’s heard before. To him it evokes the movement of a monster with no arms or legs dragging itself along the ground, among other imaginative responses. How creepy is that? Tom’s dad (who wisely does not actually appear in the pictures) explains that it’s just the scurrying of mice in the walls, which comforts Tom. But his little brother Tim can’t sleep for worrying because he doesn’t know what the word “mouse†means. Here again is a reference to the power of really understanding what words mean.

In the picture book story, Tom is awakened in the middle of the night by a sound. He sits bolt upright in bed, eyes wide and bulging. What was that? We can imagine the pounding of his heart. He can’t identify what the sound is because it isn’t like anything he’s heard before. To him it evokes the movement of a monster with no arms or legs dragging itself along the ground, among other imaginative responses. How creepy is that? Tom’s dad (who wisely does not actually appear in the pictures) explains that it’s just the scurrying of mice in the walls, which comforts Tom. But his little brother Tim can’t sleep for worrying because he doesn’t know what the word “mouse†means. Here again is a reference to the power of really understanding what words mean.

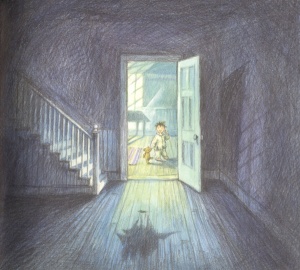

This small format book is illustrated with wonderful, semi-disheveled drawings that vividly evoke Tom’s humanity, the shadowy setting, the dim moonlight, and the bulges in the wall. One clue to the mystery of the noises is an image in which a mouse, dramatized by its long shadow, crosses a room in the foreground.

This small format book is illustrated with wonderful, semi-disheveled drawings that vividly evoke Tom’s humanity, the shadowy setting, the dim moonlight, and the bulges in the wall. One clue to the mystery of the noises is an image in which a mouse, dramatized by its long shadow, crosses a room in the foreground.

In the end, all three of these books say, in different evocative ways, that reality is what you believe it to be.

This article also appears on WritersRumpus.com.

The process of writing or illustrating a children’s has often been compared to having a baby. That gestation-to-birth time is partly the work of creating the story and pictures, but that’s just the beginning.

The process of writing or illustrating a children’s has often been compared to having a baby. That gestation-to-birth time is partly the work of creating the story and pictures, but that’s just the beginning.