This article is a post I wrote for the fabulous Writers Rumpus blog today, September 30th.

While recently reading John Green’s Looking for Alaska, I was surprised by the shape of the story. I’ll get to that in a minute, but it reminded me of other authors who played with the structure of their narratives.

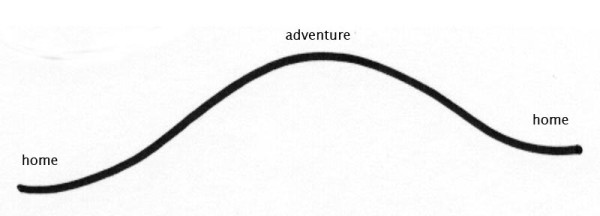

The most common description of the shape of a picture book plot, let’s say Where the Wild Things Are for example, looks something like this:

The beginning – Max being naughty in his wolf suit – can be thought of as “homeâ€, then the middle of the story is where the rumpus, adventure, quest, or struggle to resolve the problem happens, and at the end of the story Max returns “home†where his dinner is waiting, still hot. Since he has grown emotionally in the course of the story, the ending in the diagram is depicted as slightly higher than the beginning. Sendak shows this metaphorical growth by having Max’s room fill the entire page, whereas at the beginning there was a white border keeping the room smaller. Max has grown. This is a common arc-ing shape used to show the structure for a picture book story.

Novels for older kids sometimes play with structural shape that’s integral to the story. Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson, illustrated by Donna Diamond (Newbery award, 1978) takes this shape:

I was either at an SCBWI conference or at a Children’s Literature New England week-long summer conference (I attended one at Harvard and another at MIT), when I heard this explanation. Perhaps it was Jane Langton speaking? – but anyway, this is the plot analysis I heard. Bridge to Terabithia is about a boy and girl, Jesse and Leslie. Notice that both names could be either a girl’s or a boy’s, therefore interchangeable. When the story begins, Jesse is artistic, but shy and feels tormented by the kids around him. Leslie is intelligent and outgoing, though she has just moved to the neighborhood and feels ostracized. Basically, both have a lot in common, but Jesse clearly is the less dominant personality. Leslie has confidence. Jesse’s part of a conversation consists mostly of short one or two word sentences, while Leslie is more talkative and outgoing. Leslie can run faster than Jesse. He lets her take the lead in things. The two create an imaginary place called Terabithia on a real island nearby – a sanctuary from the difficulties of their lives. Leslie helps Jesse feel braver. About mid-story there is a pivotal point where he takes charge in helping Leslie and her father repair Leslie’s house. His conversation from here on becomes somewhat more open. Later, while he is at an art exhibit, Leslie drowns when the rope swing they used to cross the creek to the little island of Terabithia breaks and she falls into the current. He is devastated. As the story ends, Leslie has become the passive one, in her state of death, while Jesse is alive and struggling. Jesse’s little sister May Belle crosses the log bridge over to Terabithia, where Jesse takes on the more dominant role of helping MayBelle. In effect, Jesse and Leslie have changed places. The illustrator perfectly captures this X shape. Her soft pencil drawings show Jesse at the beginning almost always in a passive position. Then in the middle of the book there’s one image that has much stronger contrast. Jesse is holding his hands up in a most active pose. Subsequent images are the subtle grey of the earlier ones, though Jesse is in more dominant or active positions. Donna Diamond has shown the reader where the role reversal between Jesse and Leslie begins by making that image have noticeably more contrast. The author and artist have worked together to draw the plot into an X shape.

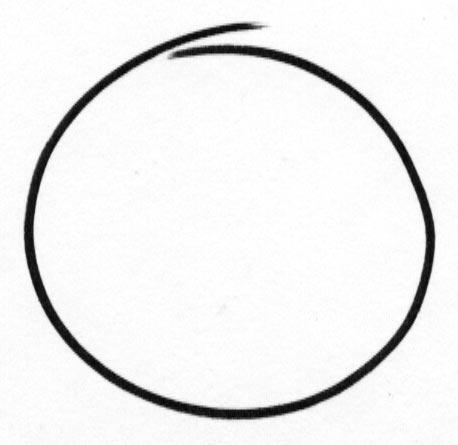

A more recent and obvious book with an unusually-shaped plot is Holes by Louis Sachar.

So much about this story is round that little explanation is needed. Stanley Yelnats is a palindrome – readable frontwards and backwards – like a circle going round and round. The holes Stanley is to dig are 5 feet wide by 5 feet deep, so you could even imagine them as spherical. The boy who helps him later in the story is named Zero and he is an ancestor of someone Stanley’s ancestor knew. When I was a student at the Museum School an art history professor asked us to write an eight-page paper about an enso – the Zen Buddist meditative symbol that is a circle made from one brush stroke. Stanley’s what-goes-around-comes-around experiences at Camp Green Lake are like an absurdist version of an enso.

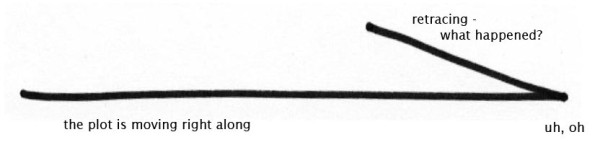

That brings me to Looking for Alaska, by the amazing John Green. When Miles Halter arrives at Culver Creek, a boarding school in Alabama, he is dropped into a group of quirky characters – the brilliant, but semi-insane Colonel (aka his roommate), Takumi – a guy of Japanese descent who has a Southern accent, and especially Alaska Young, who is supremely hot, but has a boyfriend. The plot races forward amidst much mayhem, drinking, smoking, and seriously inventive pranks involving half-drownings and fireworks. Miles is addicted to famous last words. Alaska is complex and intelligent – coming on to Miles, then pushing him away, getting drunk with him, then not speaking with him at all. Their friendship deepens, speeding forward, racing blindly on, until an amazing kiss that almost leads to…but no, Alaska suddenly takes off, leaving Miles stupidly drunk. The story abruptly comes to a crashing stop with a spectacular accident in which Alaska drunkenly dies, or kills herself. Miles, the Colonel and Takumi are devastated. And they feel guilty. They shouldn’t have let her go in that inebriated condition. Or did she kill herself? Why would she do that?

Miles sharply changes direction, and starts looking backwards for clues. One bit at a time they painstakingly reconstruct what transpired, to try to reach an understanding of any culpability they may have had. What really happened to Alaska? The story veers backward, but also upward, like one half of an arrow. By the end of the plot’s trajectory, Miles has learned as much about himself as he has about Alaska. John Green, Louis Sachar, and Katherine Paterson have all used unique story structure, plot devices that are not necessarily evident to the reader.

Have you read other stories whose plots are unusually formatted? If so, what are they and what shape do you see within them?